July 16, 2016 show

Bygone natural landmarks

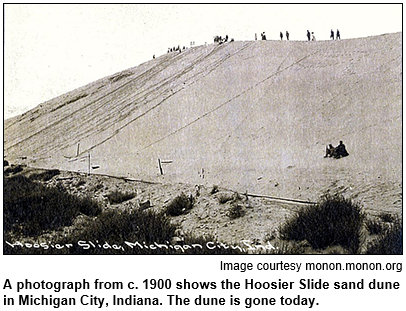

It was the biggest, by far, of the Indiana Dunes on Lake Michigan. But the Hoosier Slide, a huge, barren sand dune near Michigan City, had disappeared by 1920. It was the biggest, by far, of the Indiana Dunes on Lake Michigan. But the Hoosier Slide, a huge, barren sand dune near Michigan City, had disappeared by 1920.

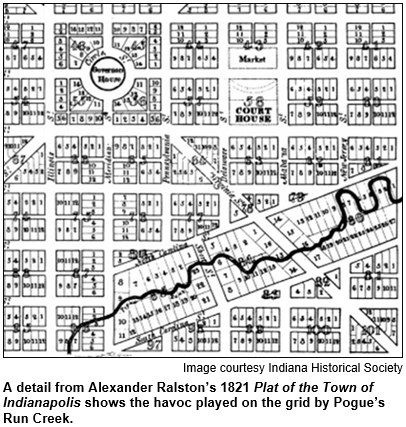

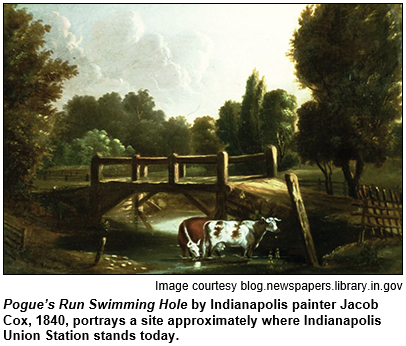

In early Indianapolis, a stream known as Pogue's Run broke the grid pattern of the Mile Square downtown. The urban creek, named after an early settler who suddenly vanished, has mostly disappeared from sight. Parts of Pogue's Run flow underneath Indy and along parkways.

What happened to these bygone natural landmarks that once were household names across the state? To share insights, Nelson will be joined in studio by two Hoosiers who have extensively researched the vanished landmarks. His guests will be:

- Christopher Taelman, a resident of Granger in far-northern Indiana who is chief development officer of the Hospice Foundation based in Mishawaka. For several years, Chris, a South Bend native and civic leader, was a manager with NIPSCO (Northern Indiana Public Service Co.). It's a utility with a generating station that now sits on the site of the legendary Hoosier Slide, which Chris calls "one of our wonders along Lake Michigan."

- And Indianapolis architect Jim Lingenfelter, owner of Five2Five Design Studio, 660 Virginia Ave. Jim, the past president of the Indianapolis Public Library Board, even embarked on a search last year with a newspaper reporter and others to try to find and follow remnants of Pogue's Run.

"In the mid-1800s, (the Hoosier Slide) had trees and berries (and) cows even grazed there," says the website emichigancity.com. "As the trees were cut and used, the dune became bare, probably by 1870.  Commercial sand mining began about 1890, when the Monon Railroad built a switching track along the south side of the dune to serve the lumber docks on the west side of the harbor." Commercial sand mining began about 1890, when the Monon Railroad built a switching track along the south side of the dune to serve the lumber docks on the west side of the harbor."

Postcards of the Hoosier Slide were distributed during the late 19th century to tout what some called "Indiana's most famous natural landmark."

According to various sources, sand from the Hoosier Slide was hauled away - initially via wheelbarrows - and was transported for use by commercial endeavors in Indiana. When natural gas was discovered in east central Indiana during the 1880s, large users of the Hoosier Slide's sand were glass-making companies that sprang up. They included the business of the Ball Brothers in Muncie.

In Indianapolis, the original planner of the new Hoosier capital, Alexander Ralston, had to modify the pattern of his grid because Pogue's Run flowed through the Mile Square.

Ralston platted the city in 1821, the same year that George Pogue, a blacksmith credited with being one of the earliest white settlers, mysteriously vanished. He disappeared after leaving his home to search for horses that may have been stolen. Ralston platted the city in 1821, the same year that George Pogue, a blacksmith credited with being one of the earliest white settlers, mysteriously vanished. He disappeared after leaving his home to search for horses that may have been stolen.  Various theories have been offered to explain why Pogue never returned from the woods, including folklore that Native Americans may have captured him. Various theories have been offered to explain why Pogue never returned from the woods, including folklore that Native Americans may have captured him.

The stream named in his honor often was regarded as a nuisance by city leaders. To open the Mile Square for development, downtown portions of Pogue's Run were routed underground.

But portions of Pogue's Run still visibly flow near Brookside Parkway on the eastside of Indy. The stream also runs through the campus of Tech High School.

Our guest Jim Lingenfelter is a Tech alum and says he, even before his high school years, "hunted for crawdads" in parts of Pogue's Run on the eastside. In addition, Jim's great-grandfather, a Purdue graduate, was an engineer who was part of the team that erected a viaduct that elevated the Union Station railroad tracks and, in 1913, created the enclosed storm sewer that continues to carry Pogue's Run underneath downtown.

Ever since the founding of Indianapolis in the 1820s, civic leaders had disparaged Pogue's Run as a mosquito-infested source of "pestilence" downtown. One of the state legislature's first appropriations involved $50 to clean up the stream in the new state capital. Because Pogue's Run was too shallow and narrow to be navigable, it was regarded as, at best, useless.

During the Civil War, after Republicans and Democrats clashed during state conventions, there even was an incident derisively known as the "Battle of Pogue's Run". Far from being a battle, the 1863 event merely involved Democrats on departing trains tossing their knives, pistols and other weapons from railcar windows into the stream. During the Civil War, after Republicans and Democrats clashed during state conventions, there even was an incident derisively known as the "Battle of Pogue's Run". Far from being a battle, the 1863 event merely involved Democrats on departing trains tossing their knives, pistols and other weapons from railcar windows into the stream.

Just as portions of the 11-mile urban stream still can be seen above ground, its name lives on in various ways. Pogue's Run Grocer on East 10th Street is touted as the city's only food cooperative.

The Hoosier Slide, though, is merely a memory. The sand dune's height was estimated at 200 feet.

According to emichigancity.com, two sand companies - including one called the Hoosier Slide Sand Co. - became competitive. They eventually used cranes and electrical conveyor belts to remove the Hoosier Slide.

Sand was shipped for business and commercial use as far away as Mexico. According to some sources, a total 13.5 million tons of sand had been hauled away by 1920, when the Hoosier Slide disappeared.

Learn more:

- Urban Trekkers Seek to Uncover Mystery of Pogue's Run - Will Higgins story in The Indianapolis Star, May 19, 2015.

- Explore Indy's rat-infested underworld - Will Higgins story in The Indianapolis Star, Oct. 31, 2013.

- Natural gas boom of 1880s and '90s - Newsletter for June 7, 2014 Hoosier History Live show.

- Long-forgotten man who designed Indy - Newsletter for Feb. 9, 2013 Hoosier History Live show.

- Uncle Archy Fires His Pistol, or Why Am I Here? - Jim Lingenfelter reading regarding Pogue's Run, April 6, 2015, Indianapolis Literary Club.

- The Pogue's Run Ghosts - May 7, 2015 account by Stephen J. Taylor in Hoosier State Chronicles.

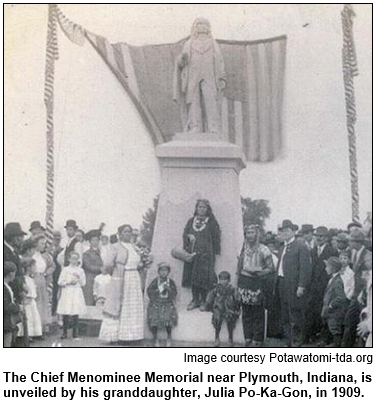

Roadtrip: Chief Menominee Memorial near Plymouth in northern Indiana

Guest Roadtripper and longtime Hoosier History Live fan Phil Brooks, who works by day as an aircraft dispatcher, invites us to visit the Chief Menominee Memorial south of Plymouth, Indiana, and west of U.S. 31 in Marshall County. It commemorates the Potawatomi Chief Menominee, who lived from the early 1790s to 1841. Guest Roadtripper and longtime Hoosier History Live fan Phil Brooks, who works by day as an aircraft dispatcher, invites us to visit the Chief Menominee Memorial south of Plymouth, Indiana, and west of U.S. 31 in Marshall County. It commemorates the Potawatomi Chief Menominee, who lived from the early 1790s to 1841.

Menominee's refusal to concede more land to the federal government led to the forced removal of his band of 859 from their village at Twin Lakes in 1838, known as The Potawatomi Trail of Death. Forty-two Potawatomi died on the two-month walk to reservation lands in Kansas. It was the single largest forced removal of Native Americans from the state of Indiana.

The 17-foot-tall granite monument was the first to honor a Native American to be dedicated in the United States under a state or federal legislative enactment. Its dedication was in 1909.

"On a lighter note," Phil tells us, "there's a popular Marshall County event that will be occurring on Labor Day weekend, the Marshall County Blueberry Festival." Held in the town of Plymouth, and celebrating its 50th year in 2016, it of course features blueberry treats of all kinds, as well as entertainment, crafts, a parade, road and swimming races. And best of all, it's free!"

History Mystery

Tech High School, through which Pogue's Run flows, was the third public high school in Indianapolis to open. Located on a 75-acre campus that was the former federal arsenal grounds used by the Union Army during the Civil War (hence, the school's official name of Arsenal Technical High School), its roots date to the early 1900s.

Shortridge High School is considered to be the oldest public high school in the Hoosier capital because it evolved from the city's first, which was known as Indianapolis High School when it opened in the 1860s.

Question: What was the second public high school to open in the city?

To win the prize, you must call in with the correct answer during the live show and be willing to be placed on the air and be willing to give your contact info to our engineer. The call-in number is (317) 788-3314, and please do not call until you hear Nelson pose the question on the air. Please do not call if you have won a prize from any WICR show during the last two months.

The prize is a Family Fourpack for admission to Conner Prairie and two tickets to a performance of Bush and Chevell at White River State Park on July 26, courtesy of Visit Indy.

Your Hoosier History Live team,

Nelson Price, host and creative director

Molly Head, producer, (317)

927-9101

Richard Sullivan, webmaster and tech director

Pam Fraizer, graphic designer

Garry Chilluffo, media+development director

www.hoosierhistorylive.org

Please tell our sponsors that you appreciate their support: Five2Five Design | Indiana Authors Award | Indiana Historical Society | Lucas Oil | Story Inn | Visit Indy | Yats Cajun Creole Restaurant

Acknowledgments to Monomedia, Visit Indy, WICR-FM, Fraizer Designs, Heritage Photo & Research Services, Derrick Lowhorn and many other individuals and organizations. We are an independently produced program and are self-supporting through organizational sponsorships and individual contributions. We do not receive any government funding. Visit our website to learn how you can support us financially. Also, see our Twitter feed and our Facebook page for regular updates. Acknowledgments to Monomedia, Visit Indy, WICR-FM, Fraizer Designs, Heritage Photo & Research Services, Derrick Lowhorn and many other individuals and organizations. We are an independently produced program and are self-supporting through organizational sponsorships and individual contributions. We do not receive any government funding. Visit our website to learn how you can support us financially. Also, see our Twitter feed and our Facebook page for regular updates.

July 23, 2016 show

Unheralded heroes of the Underground Railroad

During the 1830s in Indianapolis, a free African-American landowner named James Overall helped escaped slaves. At one point, Overall, who previously had lived in Corydon, was attacked in his Indianapolis home by a gang of white residents.

In September, a historic marker commemorating Overall will be erected on Indiana Avenue, near where he owned property.

As we explore unheralded heroes of the Underground Railroad, Nelson will be joined in studio by Corydon-based historic preservationist Maxine Brown, who has researched Overall's efforts and crusaded for the marker to be erected by the Indiana Historical Bureau.

Nelson's guests also will include Nick Patler, a former student at Bethany Theological Seminary who has researched Underground Railroad activity in Wayne County. Nick recently spoke to Indiana Freedom Trails, a nonprofit that is researching and verifying sites and people across the state involved in the Underground Railroad. Nelson's guests also will include Nick Patler, a former student at Bethany Theological Seminary who has researched Underground Railroad activity in Wayne County. Nick recently spoke to Indiana Freedom Trails, a nonprofit that is researching and verifying sites and people across the state involved in the Underground Railroad.

According to Maxine's research, James Overall and his family were listed as "free persons of color" in Corydon in the 1820 U.S. Census; he had purchased property there as early as 1817. By 1830, the family had moved to Indianapolis, where Overall became a trustee of the African Methodist Episcopal Church.

In 1836, Overall was attacked in his home by a white gang. One of the gang leaders was briefly jailed, even though Indiana law at the time prohibited blacks from testifying against whites. The gang leader was freed, but the outcry prompted a Marion County judge to write a lengthy opinion (printed in newspapers) arguing that "the natural rights of man" offered all men, including African Americans, some legal protections to defend themselves, their families and their homes.

During this period, Overall helped with Underground Railroad activity. Those he assisted included Jermain Loguen, an escaped slave from Tennessee who eventually because a well-known Underground Railroad activist based in New York. The historic marker for Overall will be dedicated Sept. 29 at 3:30 p.m.

Our guest Nick Patler will share insights about historic figures who helped escaped slaves in Richmond and elsewhere in Wayne County. Most of the attention in eastern Indiana has focused on Levi and Catherine Coffin, Quakers whose home is a state historic site.

But Nick says several unheralded others took great risks. They include Calvin Outland, a freed slave who arrived with a Quaker migration team in 1831 and who "appears to have become one of the main Underground Railroad operatives in the city of Richmond."

Other heroes include two escaped slaves: William Bush, who settled in Wayne County and, as Nick puts it, "went to work helping other African Americans fleeing bondage," and Louis Talbert, who thwarted slave hunters while helping others like himself.

Learn more:

© 2016 Hoosier History Live! All rights reserved.

|