Saturdays, noon to 1 p.m. ET on WICR 88.7 FM.

Or listen live from anywhere on WICR Online!

Our call-in number during the show: (317) 788-3314

Feb. 10, 2018

African-American health care during the early and mid-1900s

In the first half of the 20th century, an era of widespread racial discrimination in the United States, many hospitals in Indiana declined to allow African-American physicians to practice medicine or

Hoosiers seeking to serve the health-care needs of the black community persevered, however, even in the face of the daunting challenges of discrimination. Patients who could not be accommodated in overflowing "colored wards" would often be taken in by black churches.

And during the early 1900s, a hospital, a surgery center and a clinic for African-American patients were built in Indianapolis.

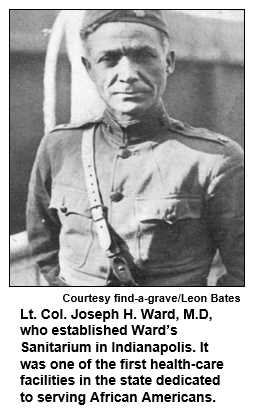

A longer-lasting facility, Ward's Sanitarium, was a surgery center and clinic in Indianapolis opened by Dr. Joseph Ward (1872-1956), a trail-blazing African-American physician. Other African-American medical pioneers included Dr. Harvey Middleton Sr. (1895-1978), a cardiologist who advocated for opportunities for black physicians to serve on the staffs of Indiana hospitals.

To discuss the health care scenario for African Americans in Indiana during the first half of the 20th Century, two guests will join Nelson in studio:

- Leon Bates, an Indianapolis-based historian who has researched the life of Dr. Joseph Ward; Ward left Indianapolis in the 1920s to become the head of Tuskegee Veterans Hospital in Alabama. (After this departure, Ward's Sanitarium, which lasted until 1938, was overseen by Ward's brother-in-law, according to Leon.)

- And Norma Erickson, a board member of the Indiana Medical History Museum. She has extensively researched the training of African-American nurses during the early 1900s as well as the history of Lincoln Hospital, which had 19 rooms and, as Norma puts it, gave black physicians "the ability to fully practice their profession." Lincoln Hospital also had a nursing school for young black women.

Norma also has written about a major, unlikely benefactor of Lincoln Hospital: none other than Carl Fisher, the flamboyant founder of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. During our show, Norma will explain why Fisher, who launched the Indianapolis 500 in 1911, took a keen interest in the hospital for African Americans.

According to our guests, City Hospital had a "colored ward" in its basement for a few black patients during the early 1900s. When the segregated ward overflowed, local churches - including Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church - often set up beds for patients.

Neither Dr. Ward nor Dr. Middleton Sr. were native Hoosiers. Dr. Ward was born in North Carolina, where his mother had been a slave. He received his medical training in Indianapolis and opened an office on Indiana Avenue in 1901. Ward's Sanitarium, which opened in 1910, also initially was located on Indiana Avenue.

"By 1922, African Americans needing surgery were coming to him from as far away as Bedford to Kokomo to Terre Haute to Richmond - a radius of approximately 100 miles," our guest Leon Bates has written. According to Leon's research, Ward also served as a medical doctor in the Army during World War I. In the war, he was one of 104 African-American physicians in the Army.

Dr. Middleton was born in South Carolina. In 1928, he moved to Anderson, Ind., to join the staff of a local hospital. He relocated to Indianapolis during the mid-1930s and established a private medical practice. As a cardiologist, Dr. Middleton began treating - as a volunteer - patients at City Hospital's outpatient heart clinic. In 1942, City Hospital invited him to serve as a full-time staff member.

“Later, he became one of the first physicians in Indiana to use EKG technology to detect heart problems,” according to Eskenazi Health.

History Mystery

In 1991, a racecar driver who grew up in California became the first African American to compete in the Indy 500. He also competed in the Indy 500 in 1993.

Question: Who was the first African-American driver to race in the Indianapolis 500?

Hint: Our mystery driver competed in many forms of auto racing, including the Trans-Am Series, IndyCar, Champ Car, IMSA, the NASCAR Sprint Cup Series and Craftsman Truck Series

The call-in number is (317) 788-3314. Please do not call in to the show until you hear Nelson pose the question on the air, and please do not try to win if you have won any other prize on WICR during the last two months. You must be willing to give your first name to our engineer, you must answer the question correctly on the air and you must be willing to give your mailing address to our engineer, so we can mail the prize pack to you. The prize is two passes to the Indiana History Center, courtesy of the Indiana Historical Society, and two passes to GlowGolf, courtesy of GlowGolf.

Roadtrip: Swope Art Museum in Terre Haute

Guest Roadtripper Rachel Berenson Perry, Indiana State Museum Fine Arts Curator Emerita and freelance historian, tells us that the Swope Art Museum in downtown Terre Haute is a gem. Although modest in proportions, the Swope has an extraordinary collection of nearly 2,500 works of American art and is well worth a visit.

The founding collection of the Swope focuses on American regionalism and includes works by Thomas Hart Benton, Edward Hoppe and Zoltan Sepeshy. The museum also features works by artists from the mid 20th to early 21st centuries, including pieces by Robert Rauschenberg, Alexander Calder, Andy Warhol, Robert Indiana and Eva Hesse.

If Indiana artists are your thing, the Swope is the place for you: one gallery is devoted to artists from the Hoosier Group, including J. Ottis Adams, William Forsyth, Otto Stark and Theodore C. Steele. Brown County Impressionists are represented by such artists as C. Curry Bohm, Carl C. Graf and Genevieve Goth Grath.

Admission to the Swope is free; hours of operation are Tuesday through Sunday noon to 5:00 pm and Friday noon to 8:00 pm.

10 years on the air!

Join us March 1 for our anniversary soiree!

Can you believe it? Hoosier History Live has been on the air 10 years.

To celebrate, we are throwing another of our famous anniversary parties!

- When: Thursday, March 1, 2018, from 5 to 7:30 p.m.

- Where: Indiana Landmarks Center, 1201 Central Ave., Indianapolis, IN 46202.

Featured events at the party will include live "History Mystery" quizzes by host Nelson Price, with fabulous prizes. Brief remarks by Indianapolis Mayor Joe Hogsett and Danny Lopez, Deputy Chief of Staff, Indiana Governor’s Office. Musical performances by Herron High School String Quartet and Shirley Judkins. Feel free to wear your historical garb, and/or sport the attire of your ethnic identity. Share remarks and good cheer with our history-loving crowd, which includes listeners, readers and of course many of our distinguished on-air guests.

Bring your Indiana photos from any era, including the present, for scanning by the Indiana Album, an online catalog of photographs from Indiana's past.

Delicious catered cuisine and cash bar provided by MBP Distinctive Catering. Let's celebrate! Click on this RSVP link today to let us know you're coming. It helps us out a lot if you use the form to let us know you'll be there!

Nelson Price, host and historian

Molly Head, producer/project manager, (317) 927-9101

Michael Armbruster, associate producer

Cheryl Lamb, marketing and administrative manager

Richard Sullivan, senior tech consultant

Pam Fraizer, graphic designer

Garry Chilluffo, special events consultant

Please tell our sponsors that you appreciate their support!

Acknowledgments to Monomedia, Visit Indy, WICR-FM, Fraizer Designs, Heritage Photo & Research Services, Henri Pensis, Chris Shoulders and many other individuals and organizations. We are an independently produced program and are self-supporting through organizational sponsorships and individual contributions. We do not receive any government funding. Visit our website to learn how you can support us financially. Also, see our Twitter feed and our Facebook page for regular updates.

Acknowledgments to Monomedia, Visit Indy, WICR-FM, Fraizer Designs, Heritage Photo & Research Services, Henri Pensis, Chris Shoulders and many other individuals and organizations. We are an independently produced program and are self-supporting through organizational sponsorships and individual contributions. We do not receive any government funding. Visit our website to learn how you can support us financially. Also, see our Twitter feed and our Facebook page for regular updates.

Thank you!

We'd like to thank the following recent, new and renewal contributors whose donations help make this show possible!

- Chuck and Cheryl Hazelrigg.

- Linda Gugin.

- Dr. William McNiece.

Feb. 17, 2018 - Upcoming

Frederick Douglass and his Indiana connections

This year marks the 2ooth anniversary of the birth of one of the greatest African-American orators and social reformers in history, Frederick Douglass (1818-1895). Although Douglass was born into slavery in Maryland and lived in New England after escaping bondage, his work as an abolitionist sent him on extensive travels, including trips to the Midwest. As a result, Douglass has more links to Indiana than many realize.

In 1843, only a few years after escaping slavery, Douglass came to Pendleton, Ind., with a small group of other abolitionists. They were assaulted by a white mob in an attack that left Douglass seriously wounded.

After achieving national fame, Douglass returned to Indiana in 1880 at age 62. This time, he visited Noblesville, where he delivered a major speech that was received positively, with extensive press coverage. During the speech, he reflected on the assault in Pendleton 37 years earlier.

As Hoosier History Live salutes Black History Month, we will explore those episodes and other connections between Douglass and Indiana. Nelson will be joined by two studio guests:

- Celeste Williams, an Indianapolis-based writer, journalist and playwright. She has written More Light: Douglass Returns, a two-act play about the statesman's visits to Indiana. With the Asante Children's Theater, the play was performed at Conner Prairie Interactive History Park last year and is expected to be performed there again this year.

- And Jack Kaufman-McKivigan, an American history professor at IUPUI who is the editor of the Frederick Douglass Papers, a national project to collect and publish all of his speeches, letters and writings. Jack also is organizing a symposium, Frederick Douglass at 200: His Living Words, that will be held Oct. 25-26 at IUPUI.

Frederick Douglass was born into slavery on a plantation in Maryland; as a youth, he was regularly whipped and beaten. After escaping at age 20, he was based in Rochester, N.Y., and Washington D.C. for most of his career.

Our guest Celeste Williams said she was encouraged to research Douglass' visits to Indiana and write her play by Noblesville resident Bryan Glover, a descendant of some of the founders of the Roberts Settlement, an historic community of African Americans in Hamilton County.

Roberts Settlement residents were instrumental in arranging for Douglass to speak in Noblesville in 1880 at a political rally for the Republican Party. Celeste says she took the title of her play from the words of Douglass' speech:

"I believed then as I do now that all the American people need is more light. I believed then if I could impress them with the idea of wrongs and cruelties suffered by the black man, if I could unfold the evils of the hideous monster - slavery - that the American people would crush and destroy it."

With the words "I believed then," Douglass alludes to his trip to Pendleton in 1843 when he and his companions were assaulted and thus unable to deliver speeches they had prepared.

In his autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, the great orator describes the Pendleton assailants as "a mob of about 60 of the roughest characters I ever looked upon."

© 2018 Hoosier History Live. All rights reserved.

|