Saturdays, noon to 1 p.m. ET on WICR 88.7 FM.

Or listen live from anywhere on WICR Online!

Our call-in number during the show: (317) 788-3314

June 29, 2019

Violent early era of Fishers: encore

It's a suburban boomtown continually in the spotlight because of developments like the opening in 2017 of the first Ikea store in the state.

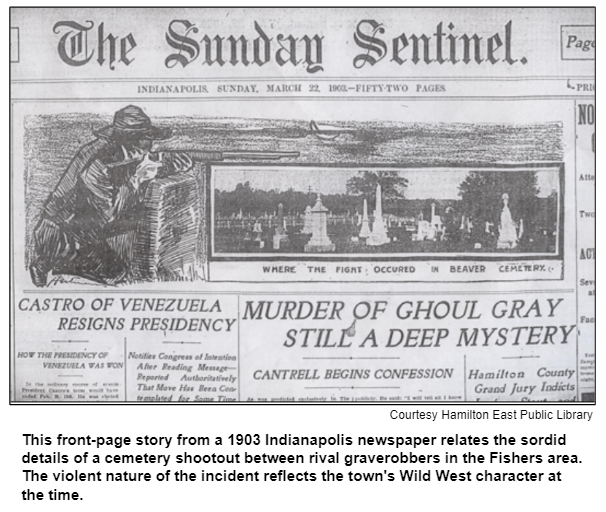

So who today would guess that Fishers, located in Hamilton County, had a reputation for lawlessness, gun fights, grave robberies and drunken brawls in the years after it was founded during the 1870s?

Even Fishers' nickname of Mudsock has violent origins: a melee known as "the Battle of Mudsock" made national news in 1881, one month after the infamous Gunfight at the O.K. Coral (in Arizona) when, according to David, the public was paying close attention to violent incidents.

"If you've seen the movie Tombstone or the TV series Deadwood - that was what Fishers was like," David contends.

He has posted several blog entries about Fisher's violent early years on a weekly blog of the Hamilton East Public Library, where he works in collection services.

Much of the blame for the Wild West early years of Fishers, David says, falls on "the loose political structure of the town," which encouraged lawlessness. As a railroad depot (the community early on was known as Fishers Station), Fishers was located near several towns with strict temperance laws and ordinances.

"So if someone wanted to raise a little hell," David says, "they would go to Fishers."

A native Hoosier and a descendant of Indiana pioneers, David is on the board of directors of the Hamilton County Historical Society and serves on the Noblesville Historic Preservation Commission.

According to an article David wrote for the Hamilton County Business Magazine, the Battle of Mudsock in November 1881 was a "community-wide brawl" that left one dead and 32 wounded. A fistfight escalated into an "explosion of violence."

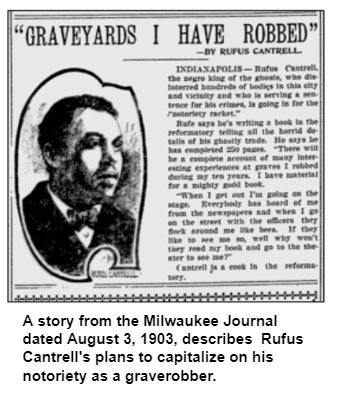

Grave robbing in the Fishers area circa 1900 was an extension of "body snatching" problems in Indianapolis, which was the epicenter of a major national ring led by Rufus Cantrell, who was known as the "King of the Ghouls."

Cantrell and his accomplices, who may have included a physician born in Hamilton County in 1859, supplied corpses to early medical schools desperate for bodies to use in teaching students. In one of David's blog posts about the grave robbery problems, he describes how Cantrell testified in court against the physician from Hamilton County.

Other crimes in early Fishers included "train wrecking," robberies in which desperadoes placed ties or other obstructions on railroad tracks. When approaching trains would crash or overturn, the criminals would loot the wreckage.

In the 1880s, when the Monon Railroad line opened in the western part of Hamilton County - the opposite end from Fishers - violence in the town began to decline, according to David. He adds, though, that a pool hall located in the back of a Fishers hardware store was demolished by a dynamite explosion in 1914.

"By the end of World War I," he notes, Fishers "had begun to settle into a quiet farming community."

Roadtrip: Garfield Park's Confederate memorial revisited

With Confederate monuments in the news and causing controversy around the country, guest Roadtripper and architectural historian William Selm invites us to explore Garfield Park's Confederate memorial.

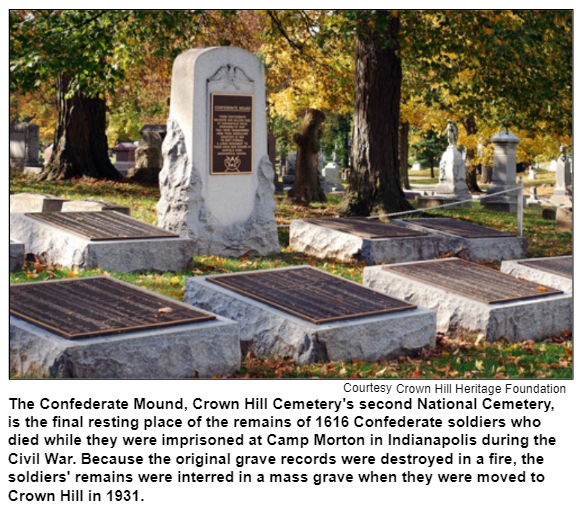

Bill explains that the memorial was originally placed in the old Greenlawn Cemetery in downtown Indianapolis in 1910. It read "Erected by the United States to mark the burial place of the 1616 soldiers and sailors who died while prisoners of war and cannot now be identified."

Basically these 1616 men died between 1862 and 1865 while Confederate prisoners of war at Camp Morton, in what is now Herron Morton Place in Indianapolis. Their remains were moved quite a few times, from Camp Morton to Greenlawn Cemetery and finally to what is now called the Confederate Mound in Crown Hill Cemetery.

Meanwhile, the memorial was moved from the then-closing Greenlawn Cemetery to Garfield Park on the south side of Indianapolis in 1929.

Learn more:

- Laura McPhee, Nuvo, August 22, 2017, The Long Controversial History of Garfield Park's Confederate Monument.

- Paul Mullins, Archeology and Material Culture, Aug. 28, 2017, Race, Reconciliation, and Southern Memorialization in Garfield Park.

They're singing our praises!

"Hoosier History Live is the best Americana-themed show anywhere on radio!"

So says John Guerrasio, a professional actor who lives in London, England. We met John in 2008 when he played a role in the Indiana Repertory Theatre's production of The Ladies Man, a French farce by Georges Feydeau.

Even though he no longer lives in Indiana, John stays current with Hoosier History Live by listening to the show via podcast. He encourages other listeners to do the same - wherever they live. Listening by podcast means you can catch up on old shows, post shows on your social media accounts, and fit your listening to your own schedule.

Just go to hoosierhistorylive.org and look for recent shows linked in bold typeface at the top of the site. For older shows check out our archive page, where podcast links are available along with the original newsletter material for each show. You can also access Hoosier History Live podcasts via Apple's podcast app on your phone or iPad, or many other podcasting apps as well.

Whether you listen live on Saturdays or via podcast, we think you'll agree with John that Hoosier History Live is worth making a part of your day!

Nelson Price, host and historian

Molly Head, producer/project manager, (317) 927-9101

Michael Armbruster, associate producer

Cheryl Lamb, administrative manager

Richard Sullivan, senior tech consultant

Pam Fraizer, graphic designer

Garry Chilluffo, special events consultant

Please tell our sponsors that you appreciate their support!

Acknowledgments to Monomedia, Visit Indy, WICR-FM, Fraizer Designs, Heritage Photo & Research Services, Henri Pensis, Aaron Duvall, Chloe Tyson, and many other individuals and organizations. We are independently produced and are self-supporting through organizational sponsorship and through individual contribution at the yellow button on our newsletter or website. For organizational sponsorship, which includes logos, links, and voiced credits in the show, contact Molly Head at (317) 927-9101 or email her at molly@hoosierhistorylive.org. Our media reach continues to grow via podcasting and iTunes.

Acknowledgments to Monomedia, Visit Indy, WICR-FM, Fraizer Designs, Heritage Photo & Research Services, Henri Pensis, Aaron Duvall, Chloe Tyson, and many other individuals and organizations. We are independently produced and are self-supporting through organizational sponsorship and through individual contribution at the yellow button on our newsletter or website. For organizational sponsorship, which includes logos, links, and voiced credits in the show, contact Molly Head at (317) 927-9101 or email her at molly@hoosierhistorylive.org. Our media reach continues to grow via podcasting and iTunes.

Thank you!

We'd like to thank the following recent, new and renewal contributors whose donations help make this show possible!

- Perry and Melanie Hammock

- Jim and Bonnie Carter

- Barbara and Michael Homoya

- Noraleen Young

- Barbara Wellnitz

- Phil and Pam Brooks

- Russ Pulliam

- Roz Wolen

- Marion Wolen

- Richard Vonnegut

- Robin Jarrett

July 6, 2019 - coming up

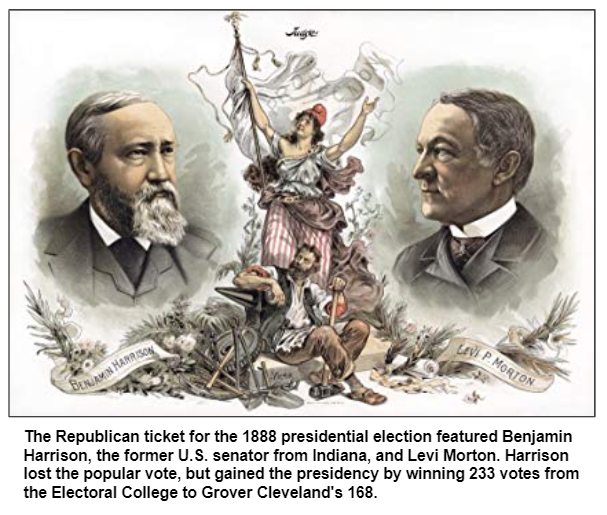

Electoral College upset, souvenir hunters and no campaigning: 1888 and 1892 presidential races

Because of the attention focused on the Electoral College in the 2016 presidential race - in which the winner did not gain the most popular votes - it may not be surprising that a similar situation unfolded in 1888.

That's what happened in 1892 - in sharp distinction to the current situation in which intense campaigning is in full swing more than 18 months before voters go to the polls.

Both the 1888 and 1892 campaigns featured Benjamin Harrison of Indianapolis as the Republican candidate for the White House. And both unfolded during an era - stretching from the 1870s through the 1920s - in which Indiana was regarded nationally as a "swing state" in presidential elections.

As evidence: Harrison did not carry his home state in 1892 (a majority of Indiana voters preferred his Democratic opponent, Grover Cleveland), although Harrison, a former U.S. senator from Indiana, won the Hoosier State in 1888. His "front porch campaign" that year - based out of his Italianate home that is now part of the Benjamin Harrison Presidential Site at 1200 N. Delaware Street - resulted in scores of souvenir hunters who tore off pieces of the property's wooden fence. Caroline Scott Harrison, who would become the nation's first lady, is said to have remarked: "If we don't go to the White House, we'll go to the poor house, with all of the repairs we'll have to make."

To share insights about colorful and intriguing aspects of Harrison's presidential campaigns, Nelson will be joined by Ray Boomhower of the Indiana Historical Society, the author of the new biography Mr. President: A Life of Benjamin Harrison (IHS Press).

In contrast, the 1888 campaign - which also featured Harrison against Cleveland - was a lively affair. One of the more memorable publicity ploys: Harrison's supporters built a massive, steel-rigged, canvas ball, covered it with campaign slogans and travelled over 5,000 miles with it to the candidate's Indianapolis home.

Harrison achieved the presidency that year by winning the Electoral College (with 233 votes to 168 for Cleveland), although he lost the popular vote. That was the third of five times in American history in which the loser of the popular vote won the Electoral College - and, as a result, the White House.

Of the six vice presidents who have been elected from Indiana, four of them achieved office during the era when Indiana was considered a swing state in national elections and was therefore courted by both parties. The Hoosier vice presidents during that era include two Democrats - Thomas Hendricks (who was in office for one year only, 1885) and Thomas R. Marshall (who served from 1913-1921) - and two Republicans, Schulyer Colfax (veep from 1869-1873) and Charles Fairbanks (1905-1909).

Ray and Nelson will discuss the factors that resulted in Indiana's swing state reputation then, in contrast to its general tendency to support Republicans in national elections in recent decades.

© 2019 Hoosier History Live. All rights reserved.

|